Paul Hindemith |

About Life and Work and Effect

Part I

„When one goes to a tailor, one doesn't want a picture or photograph of him, but a well-made suit. If someone wants to occupy himself with me, he should look at my works.“

This quote from Hindemith is almost daunting when you want to deal with the artists biography. Nevertheless, let us look at the background of the composer, who in the twentieth century has enriched the repertoire of bratschists like no other.

Childhood and Youth

On November 16th, 1885, Paul Hindemith was born. His father, Robert Rudolf Hindemith, worked as a painter. His mother, Marie Sophie Hindemith, helped out in other households to secure the livelihood for Paul and his younger siblings Antonie and Rudolf. In 1900, the family moved from Rodenbach near Hanau, to Mühlheim am Main and in 1905 to Frankfurt am Main.

On November 16th, 1885, Paul Hindemith was born. His father, Robert Rudolf Hindemith, worked as a painter. His mother, Marie Sophie Hindemith, helped out in other households to secure the livelihood for Paul and his younger siblings Antonie and Rudolf. In 1900, the family moved from Rodenbach near Hanau, to Mühlheim am Main and in 1905 to Frankfurt am Main.The father of Paul Hindemith himself wanted to be a musician, which had not been approved by his father. This might be the reason, why he was so ambitious to provide a musical education to his children, from a small age. Paul (violin), Antonie (piano) and Rudolf (cello) performed as the "Frankfurter Kindertrio" and received much plaudit and compliment.

The Study Period at the Frankfurt Music Academy, First Employments

At the age of 14, Paul finished school as the best pupil. But a further school education exceeded the budgeting possibilities of the family. His former violin Teacher, Anna Hegner acquainted Paul Hindemith to Adolph Rebner. Rebner then offered Hindemith a scholarship for the Frankfurt Music Academy (Hoch'sches Konservatorioum), start in the winter semester of 1908.

At first, he only visited Rebner's violin-class. Later, he also studied with Arnold Mendelssohn (composition), Bernhard Sekles (composition), Karl Breidenstein (score) and Fritz Bassermann (conducting). Hindemith focused on the instrumental study. Not least because, by private lessons, concerts and the absence representation of Rebner, he made an early financial contribution to his family.

Already during his studies, in 1913 he received his first job as concertmaster at the orchestra of the "New Theater" Frankfurt. At the age of 19, he was appointed second concertmaster and first violinist of the Frankfurt Opera House. Later, beginning in spring 1916, he was the first concertmaster. As a musical Jack of all trades, he took advantage of his absolute hearing, all his life.

The first successful Compositions and the Rebner-Quartett

The first successful Compositions and the Rebner-QuartettIn 1915, he received a prize from the Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy Foundation for the submission of his “Streichquartett in C-Dur” Op. 2 (String Quartet in C Major" Op. 2). In the same year he received a high-quality violin for winning a competition (Joseph-Joachim-Preis).

Also in 1915 he became a member of his teacher's quartet (the Rebner-Quartett). This he left later in 1921, after disagreements with Rebner. The repertoire of the Rebner Quartet, which was too old-fashioned for the young, modern Hindemith, was the main reason for the disengagement.

The First World War

At the beginning of World War I, in the summer of 1914, Hindemith was a violinist at an ensemble in a cure village in Switzerland. At that time, Hindemith was willing to go to war. He wrote in a letter: "If I had been here from the beginning of the war, I would have long been in France, but I experienced the Swiss agitation instead of the German enthusiasm and thus missed the chance of serving my fatherland.“ In 1915 Hindemith's father fell in France, after voluntarily joining the fighting forces at the age of 44. In 1917 Paul Hindemith was then called up for military service himself. After his initial stationing in Frankfurt in 1918, he was deployed as a military musician in Alsace. Here Hindemith experienced the horrors of the First World War, but after all, he survived him unscathed.

The Early Work

"I had probably always written, but it was only after I had used up mountains of manuscript paper alongside my activity as an instrumentalist and after several of my works had appeared in print that I started to believe, at about age 24, in my compositional talent."

"I had probably always written, but it was only after I had used up mountains of manuscript paper alongside my activity as an instrumentalist and after several of my works had appeared in print that I started to believe, at about age 24, in my compositional talent."Only a few pieces of his early work were published in his lifetime. He later commented on his early work as "old-fashioned stuff" and "entirely unenjoyable." Most of the pieces were published from the inheritance, ten years after the death of Paul Hindemith.

In 1919 the first collaboration began with the Schott publishing company, the only publishing company with which Hindemith worked. In 1922 a contract was concluded, which gave Hindemith a monthly fee, after which he was able to renounce his appointment as concertmaster of the Frankfurt Opera.

The Golden Twenties, Amar Quartet, Expressionism and the Marriage

In the 1920s Hindemith played a decisive role in the landscape of contemporary music with the Amar Quartet (named after the first violinist Licco Amar, even though Paul Hindemith was already the most prominent quartet-member at the time). Rudolf Hindemith, Paul's brother, was part of the Amar Quartet as a cellist for a period.

Rudolf Hindemith later became conductor and composer, although not as successful as his older brother.

In the Amar Quartet, Paul Hindemith played the viola and was regarded as one of the best violinists worldwide in the 1920s. The Amar Quartet was active, far beyond the German borders and often helped contemporary pieces to premiere. The most attention came when Hindemith's plays were performed. A critic wrote in 1927:

"Hindemith writes for his viola, his quartet, so that they follow his lead, only that his viola part sometimes jerks through the ensemble like a snake and carries everything away with it. The result is that the artists can perform their pieces in a tempo that would make one dizzy without sacrificing a single note. For example, if the first movement of the ‹String Trio› (Op. 34) could be performed more modestly, it might be seen that the piece is actually quite pretty."

His work in the Amar Quartet ended Hindemith in 1929. At that time, he was acknowledged internationally, both

as a composer and interpreter of world rank.

as a composer and interpreter of world rank.In 1923 he had a medieval tower, the „Kuhhirtenturm“ in Frankfurt, renovated as an apartment. Hindemith was able to finance this through a particular composition order. He composed the "piano music with orchestra (piano: left hand)" op. 29 for the Austrian pianist Paul Wittgenstein who had lost his right arm in the First World War. But Wittgenstein did not perform the piece himself. It was only in 2004 that the world premiere took place with the „Berliner Philharmoniker.“ Hindemith lived in the tower with his sister, his mother, and later his wife.

The tower was destroyed in the Second World War but rebuilt afterward. Today the "Hindemith Kabinett“, which was established by the „Foundation Hindemith Institute,“ is located in the „Kuhhirtenturm.“

In 1924 Paul Hindemith married Johanna Gertrude Rottenberg. Gertrude, who trained as an actress and singer, supported Hindemith in his artistic working. After the death of Hindemith, she also began to archive his works. The marriage remained childless.

His early compositions of the 1920s are in part very expressionistically, some of them caused scandals during their performances. For example, the performance of the "Lehrstück" (a collaboration with Berthold Brecht), in which a man is sawn to pieces, or the singular one-act "Sancta Susanna", the second part of a tryptichon, framed by the first part "Mörder, Hoffnung der Frauen" (After Oskar Kokoschka) and the third part "Nusch Nuschi."

The Move to Berlin

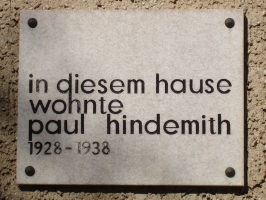

In 1927 Hindemith received a professorship for composition at the Berlin College of Music, from 1929 he also taught at the new music school in Neukölln.

In 1927 Hindemith received a professorship for composition at the Berlin College of Music, from 1929 he also taught at the new music school in Neukölln.In Berlin, Paul and his wife Gertrud Hindemith moved into a new settlement in the quarter Westend. Hindemith made friends with other artists, including Igor Stravinsky and Franz Schreker. He also met numerous distinguished writers, including Berthold Brecht, Carl Zuckmayer, and Alfred Döblin. Here in Berlin, Hindemith made his driving license, he learned mathematics and Latin and developed an enthusiasm for sports.

After completing his work in the Amar Quartet in 1929, Hindemith played in a string trio together with Emanuel Feuermann and Joseph Wolfsthal, who was replaced by Szymon Goldberg after his death.

Hindemith often performed as a soloist at orchestral concerts, which also inspired his compositional work of solo concerts for the viola. For example, his "Kammermusik Nr. 5" Op. 35, the "Konzertmusik für Solobratsche und größeres Kammerorchester" Op. 48.

As a soloist, he played the premiere of the viola concerto of William Walton in 1929. At the same time, Darius Milhaud dedicated Hindemith his violin concerto, which Hindemith also premiered.

Hindemith was also in great demand as a composer. He received composition order for the Frankfurter Rundfunk, the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Festival in Washington and the 50th anniversary of the Boston Symphony Orchestra.

The Festivals of Donaueschingen and Baden-Baden

A real boost to Hindemith's career and those of the Amar Quartet were the festivals "Donaueschinger Musiktage," where he premiered several of his plays. The performance of his “third String Quartet” Op. 16 (with the Amar Quartet) in 1921, made Hindemith widely known. From 1923, Hindemith was also active on the music committee of the „Donaueschinger Musiktage.“

A real boost to Hindemith's career and those of the Amar Quartet were the festivals "Donaueschinger Musiktage," where he premiered several of his plays. The performance of his “third String Quartet” Op. 16 (with the Amar Quartet) in 1921, made Hindemith widely known. From 1923, Hindemith was also active on the music committee of the „Donaueschinger Musiktage.“In 1927, they changed place and became known as "Deutsche Kammermusik Baden-Baden" (German Chamber Music in Baden-Baden). There, under the title original music for broadcasting, the "Lindberghflug" was performed. It was a cooperation between Hindemith, Berthold Brecht and Kurt Weill.

Brecht later described the collaboration with Hindemith as a "misunderstanding". At first, Weill and Hindemith had written the music for the premiere in equal parts, but later Weill also worked over Hindemith's passages.

The discord between Hindemith and Brecht came in 1930 when the program committee of the festival "Neue Musik Berlin 1930" - which Hindemith belonged to - rejected a political play by Eisler and Brecht due to the fact that the focus of the festival was musical, not political. Brecht and Eisler called this decision a political censorship.

Composing between Expressionism, „New Objectivity“ and „Music for Use“

Hindemith grouped his music as follows: "One will always distinguish between two contrary types of music-making: performance and playing for one's self. Performance is the profession of the musician, playing for one's self is occupation for amateurs."

Hindemith grouped his music as follows: "One will always distinguish between two contrary types of music-making: performance and playing for one's self. Performance is the profession of the musician, playing for one's self is occupation for amateurs."The latter he called "Gebrauchsmusik“, meaning music for use. In this context, we can understand his foreword to the cantata "Frau Musika" Op. 45, Nr. 1: "This music is written neither for the concert hall nor for the artist. Its intention is to provide interesting and novel practice material for people who want to sing and play for their own enjoyment, or perform for a small circle of kindred spirits."

Dr. Schaal-Gotthardt, director of the Hindemith Institute Frankfurt, described this change in Hindemith's style of composition as a "consolidation of the compositional means [...] what in the early 1920s was wild and impetuous (for example the" Finale 1921 "Kammermusik Nr. 1, Op. 24, Nr. 1), later became firmly structured, also tonally more strongly founded."

This change of direction was inspired by his work "The Marienleben" Op. 27 (after Rainer Maria Rilke). He commented, "I like the pieces very much and am glad that I succeeded so well. I am sure that they are now the best I have done..."

Later, he said, "The strong impression already made by the first performance on the listeners – I had expected nothing – made me aware, for the first time in my life as a musician, of the ethical necessity of music and the moral obligations of the musician..."

These findings resulted in a creative phase of Hindemith, which is described as "New Objectivity." Instead of the eccentric and provocative, his working showed a sobriety, a formality in the music, which was inserted into the social-cultural interweaving of its time. A piece that can be cited as an example of "New Objectivity" is the "Kammermusik Nr. 5” Op. 36 Nr. 4, also called Viola-Concert.

In this Blog, you will find the next article „Paul Hindemith - About Life, Work and Effect, Part II“ about the artist's work since the 1930s, the confrontations with the Third Reich and the following areas of influence.

Sources and further reading:

http://www.hindemith.info

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Der_Flug_der_Lindberghs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Hindemith

Pictures:

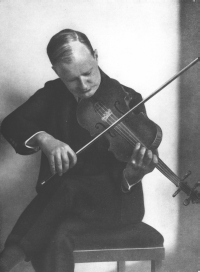

Paul Hindemith in uniform with violin 1918: http://www.hindemith.info/fileadmin/1

The Amar Quartett with Igor Strawinsky, 1924: http://www.hindemith.info/fileadmin/2

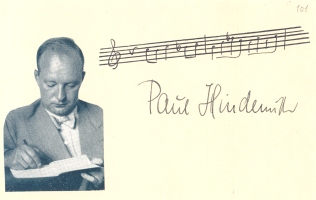

Paul Hindemith 1928: http://www.hindemith.info/fileadmin/3

Sound examples online:

Der Lindberghflug

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fvRyBWnxKl4

Musik: Kurt Weill & Paul Hindemith, Text: Berthold Brecht

Sonate für Viola und Klavier, op 11 Nr 4

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zzKs4JV9-qo

Viola: Juri Abramowitsch Baschmet, Klavier: Sviatoslav Richter, Moscow in 1985.

Part II

Here you will find part II of Paul Hindemith "From Life, Work and Effect" ...

A blog article by Mascha Seitz.

Pictures: © Fondation Hindemith, Blonay (CH)

Add comment

| Blog overview |

» To the blog list

| Newsletter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our newsletter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our newsletter will keep you informed.» Subscribe to our Newsletter for free

Visit us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.

Visit us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.» To Facebook