|

Harold en Italie |

by Mascha Seitz

Hector Berlioz wrote his second symphony ”Harold en Italie,” - Symphonie en quatre parties avec un alto principal, Op. 16 [H 68*] in 1834. It consists of four movements and contains an extensive part for the solo viola. The premiere took place on November 23, 1834, performed with the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire. The solo viola was played by Chrétien Urhan (violist, violinist, organist and composer) and the concert was conducted by Narcisse Girard (conductor, violinist and composer).

Hector Berlioz wrote his second symphony ”Harold en Italie,” - Symphonie en quatre parties avec un alto principal, Op. 16 [H 68*] in 1834. It consists of four movements and contains an extensive part for the solo viola. The premiere took place on November 23, 1834, performed with the Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire. The solo viola was played by Chrétien Urhan (violist, violinist, organist and composer) and the concert was conducted by Narcisse Girard (conductor, violinist and composer).This work by Berlioz is of outstanding significance for the viola. Above all, prior to the time of writing, noteworthy literature for the viola was unavailable. In 1843, Berlioz wrote in Treatise on Instrumentation about the viola, noting that the deep strings have a “peculiarly strong sound”, while the high strings present a “sad, passionate expression”. He also noted that the instrument is particularly suitable for “scenes of religious and antique character”. He further wrote, “Of all the instruments in the orchestra, the viola is the one whose excellent qualities have long been misunderstood”. (See also input here...)

Historical background

Niccolò Paganini was regarded as the greatest violin virtuoso during his time, and commissioned Berlioz to write a piece including a viola solo. Paganini had recently received a viola by Stradivarius and was now looking for a worthy piece for his new instrument.Berlioz, who wanted to avoid allowing the orchestra to fade away in the background, had planned some breaks for the viola part. In reference to his play, Berlioz said that he had the intention “to write a series of orchestral scenes in which the solo viola would be involved as a more or less active participant, while retaining its own character”. This, however, was not Paganini's intention. After seeing a sketch of the first movement, he declared that it wouldn’t work because he would be silent for too long and wanted to play the viola continuously. Disillusioned with each other, the paths of the two musical geniuses parted. Perhaps this is the reason why, during the course of the four movements, the participation of the solo violas decreases more and more. (See also the work «Harold en Italie» here...)

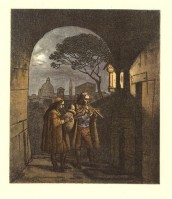

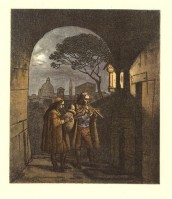

It w

as not until 1838 that Paganini heard his commissioned piece. Overwhelmed, he pulled Berlioz on the stage and kissed his hand while kneeling. This scene was later immortalized in a copper engraving (see image). The following day, Paganini's twelve-year-old son, Achille, handed Berlioz 20,000 francs and his father’s letter full of praise.

as not until 1838 that Paganini heard his commissioned piece. Overwhelmed, he pulled Berlioz on the stage and kissed his hand while kneeling. This scene was later immortalized in a copper engraving (see image). The following day, Paganini's twelve-year-old son, Achille, handed Berlioz 20,000 francs and his father’s letter full of praise."My dear friend, Beethoven being dead, only Berlioz can make him live again; and I who have heard your divine compositions, so worthy of the genius you are, humbly beg you to accept, as a token of my homage, twenty thousand francs, which Baron de Rothschild will remit to you on your presenting the enclosed.

Believe me ever your most affectionate friend,

Nicolò Paganini"

In comparison, Berlioz had received a mere payment of 3000 francs for his requiem the year before.

Hector (Berlioz) en Italie

Hector Berlioz traveled around Italy for 15 months from 1831-32. The Prix de Rome, awarded by the Paris Conservatoire, included a scholarship and a  stay at the Villa Medici, which allowed him to remain in Italy.

stay at the Villa Medici, which allowed him to remain in Italy.

During his time in Italy, long walks brought him closer to the music of ordinary people. About the influence from his journey on writing Harold en Italie, he wrote in his memoirs that he placed the viola “among the poetic memories formed from my wanderings in Abruzzi”.

Relations to Lord Byron's "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage"

The poems of Lord Byron accompanied Berlioz during his expeditions in Italy. It was during this period that he wrote Lélio ou la retour à la vie, a play inspired by Byron's work. The first sketches for the overture Le corsaire (based on Byron's poem The Corsair) were drafted during this period, as well.

Harold en Italie features the viola, which should—according to Berlioz—correspond to that of a “melancholy dreamer in the manner of Byron’s Childe-Harold”. He refers here to the lengthy romantic poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

The following lines from the third canto of the romance enable us to acquire an impression of the heroic type of characters which emerged again and again during the Romantic period, especially in Lord Byron’s works. They were often melancholic, sensitive, in conflict with society, and desired to escape from the agony of bourgeois existence and to become one with nature.

I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me; and to me,

High mountains are a feeling, but the hum

Of human cities torture: I can see

Nothing to loathe in Nature, save to be

A link reluctant in a fleshly chain,

Classed among creatures, when the soul can flee,

And with the sky, the peak, the heaving plain

Of ocean, or the stars, mingle, and not in vain.

stay at the Villa Medici, which allowed him to remain in Italy.

stay at the Villa Medici, which allowed him to remain in Italy.During his time in Italy, long walks brought him closer to the music of ordinary people. About the influence from his journey on writing Harold en Italie, he wrote in his memoirs that he placed the viola “among the poetic memories formed from my wanderings in Abruzzi”.

Relations to Lord Byron's "Childe Harold's Pilgrimage"

The poems of Lord Byron accompanied Berlioz during his expeditions in Italy. It was during this period that he wrote Lélio ou la retour à la vie, a play inspired by Byron's work. The first sketches for the overture Le corsaire (based on Byron's poem The Corsair) were drafted during this period, as well.

Harold en Italie features the viola, which should—according to Berlioz—correspond to that of a “melancholy dreamer in the manner of Byron’s Childe-Harold”. He refers here to the lengthy romantic poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage.

The following lines from the third canto of the romance enable us to acquire an impression of the heroic type of characters which emerged again and again during the Romantic period, especially in Lord Byron’s works. They were often melancholic, sensitive, in conflict with society, and desired to escape from the agony of bourgeois existence and to become one with nature.

I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me; and to me,

High mountains are a feeling, but the hum

Of human cities torture: I can see

Nothing to loathe in Nature, save to be

A link reluctant in a fleshly chain,

Classed among creatures, when the soul can flee,

And with the sky, the peak, the heaving plain

Of ocean, or the stars, mingle, and not in vain.

Contents of the four movements

The first movement “Harold aux montagnes” refers to experiences of the character Harold while in the mountains. Harold’s mixed feelings are portrayed by the slow, melancholic main theme—the opening melody of the viola—and the lively sonata movement afterwards. Byron makes the extent to which Harold is spellbound by the beauty of nature very clear.

In the second movement, “Marche des pèlerins” Harold travels with a group of pilgrims. Slowly, the violin integrates itself to represent “singing of the pilgrims”, which takes shape as a crescendo, then slowly fades, as if the group has moved on.

In the third movement, “Sérénade”, a love scene takes place. A serenade is played for someone’s loved one in Abruzzo. Harold, though he wants to escape any connections to other human beings, is confronted with the power of love: “the tender mystery” as it is described in the original text. Berlioz remarked about the third movement, “I then heard the pifferari** on their home ground, and while I had found them remarkable in Rome, once in the wild Abruzzi mountains, where my wandering fancy had taken me, I was moved by them even more”. The sounds of the pifferari (wandering musicians) can be heard in his symphony by means of the oboe, piccolo, and the bagpipe's bordone sounds, imitated by the divided violas.

In the third movement, “Sérénade”, a love scene takes place. A serenade is played for someone’s loved one in Abruzzo. Harold, though he wants to escape any connections to other human beings, is confronted with the power of love: “the tender mystery” as it is described in the original text. Berlioz remarked about the third movement, “I then heard the pifferari** on their home ground, and while I had found them remarkable in Rome, once in the wild Abruzzi mountains, where my wandering fancy had taken me, I was moved by them even more”. The sounds of the pifferari (wandering musicians) can be heard in his symphony by means of the oboe, piccolo, and the bagpipe's bordone sounds, imitated by the divided violas.

In the fourth movement, “Orgie de brigands”, Harold is beneath the brigands. Unlike those in Byron's The Corsair or Scott's Rob Roy, to which Berlioz had written an overture, these brigands are not noble figures who rebel against the shadows of society. In stark contrast, Berlioz describes his fourth movement as a “frenzied orgy, where the intoxication of wine, blood, joy, and anger come together. Where the rhythm soon stumbles, sometimes drifts forward, where curses are thrown out of the metal mouth and blasphemies respond to pleading voices, where one laughs, drinks, beats, breaks, kills, desecrates, and finally amuses [...] while the solo viola, the dreamer Harold, fleeing frightened, lets a few trembling sounds of his evening song be heard in the distance”.

The viola begins to sound the counterpoint of the fugue theme, then recalls the procession singing and the “Sérénade”, the melody of the Allegro, and its reference theme from the Adagio. Then the violin is silent until the end of the movement, where the procession song is heard again.

Adolf Nowak writes about this in Fluchtpunkt Italien:

Berlioz shows how the protagonist, in the form of the solo viola, finds something other than what he himself brings in. They are the manifestations of what cannot be ruled: the “outgrowing” of mountains, religion, love, and, finally, the horror of evil. Also, the music shows how he adapts to these experiences: the spatial expanse through “his” theme, the faithful and the lovers by contrasting and tuning into their melody; the evil, despite its fascinating presentation, by not tuning in and by reflection of the past good.

brings in. They are the manifestations of what cannot be ruled: the “outgrowing” of mountains, religion, love, and, finally, the horror of evil. Also, the music shows how he adapts to these experiences: the spatial expanse through “his” theme, the faithful and the lovers by contrasting and tuning into their melody; the evil, despite its fascinating presentation, by not tuning in and by reflection of the past good.

Berlioz was not attached too closely to his literary work. What was important to him was the mood, character, and feeling that linked his Harold en Italie to the hero of Byron. When the harp sounds in the first movement, reference is made to Childe Harold's Pilgrimage:

Performances and reworking

Although the previously discussed premiere was a complete success, following it, Berlioz decided to conduct his plays by himself.

On February 4, 1937, Lionel Tertis as a soloist, made his last public appearance as a soloist. Harold en Italie was performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Ernest Ansermet.

In 1944, the first studio recording of the work was performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, featuring William Primrose as a soloist. It was conducted by Serge Koussevitzky.

Harold en Italie was reworked in 1836 by Franz Liszt for piano, accompanied by viola.

Sources:

https://www.ndr.de/orchester_chor (PDF)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_en_Italie

http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch (Buch einsehen)

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pifferari

Vanishing point Italy: A decree for Peter Ackermann, edited by Johannes Volker Schmidt and Ralf-Olivier Schwarz

http://www.viola-in-music.com/Harold-in-Italy

http://www.helmut-zenz.de/berlioz

* Dallas Kern Holoman, Catalogue of the works of Hector Berlioz, (= Hector Berlioz. New edition of the complete works, Bd. 25), Kassel u.a. 1987, S. 138 ff.

**Pifferari: Shepherds from Abruzzi, who played reedpipes, bagpipes, and sang monotonously. During Christmas time, they came to Rome to play in front of pictures of the Virgin Mary.

The first movement “Harold aux montagnes” refers to experiences of the character Harold while in the mountains. Harold’s mixed feelings are portrayed by the slow, melancholic main theme—the opening melody of the viola—and the lively sonata movement afterwards. Byron makes the extent to which Harold is spellbound by the beauty of nature very clear.

In the second movement, “Marche des pèlerins” Harold travels with a group of pilgrims. Slowly, the violin integrates itself to represent “singing of the pilgrims”, which takes shape as a crescendo, then slowly fades, as if the group has moved on.

In the third movement, “Sérénade”, a love scene takes place. A serenade is played for someone’s loved one in Abruzzo. Harold, though he wants to escape any connections to other human beings, is confronted with the power of love: “the tender mystery” as it is described in the original text. Berlioz remarked about the third movement, “I then heard the pifferari** on their home ground, and while I had found them remarkable in Rome, once in the wild Abruzzi mountains, where my wandering fancy had taken me, I was moved by them even more”. The sounds of the pifferari (wandering musicians) can be heard in his symphony by means of the oboe, piccolo, and the bagpipe's bordone sounds, imitated by the divided violas.

In the third movement, “Sérénade”, a love scene takes place. A serenade is played for someone’s loved one in Abruzzo. Harold, though he wants to escape any connections to other human beings, is confronted with the power of love: “the tender mystery” as it is described in the original text. Berlioz remarked about the third movement, “I then heard the pifferari** on their home ground, and while I had found them remarkable in Rome, once in the wild Abruzzi mountains, where my wandering fancy had taken me, I was moved by them even more”. The sounds of the pifferari (wandering musicians) can be heard in his symphony by means of the oboe, piccolo, and the bagpipe's bordone sounds, imitated by the divided violas.In the fourth movement, “Orgie de brigands”, Harold is beneath the brigands. Unlike those in Byron's The Corsair or Scott's Rob Roy, to which Berlioz had written an overture, these brigands are not noble figures who rebel against the shadows of society. In stark contrast, Berlioz describes his fourth movement as a “frenzied orgy, where the intoxication of wine, blood, joy, and anger come together. Where the rhythm soon stumbles, sometimes drifts forward, where curses are thrown out of the metal mouth and blasphemies respond to pleading voices, where one laughs, drinks, beats, breaks, kills, desecrates, and finally amuses [...] while the solo viola, the dreamer Harold, fleeing frightened, lets a few trembling sounds of his evening song be heard in the distance”.

The viola begins to sound the counterpoint of the fugue theme, then recalls the procession singing and the “Sérénade”, the melody of the Allegro, and its reference theme from the Adagio. Then the violin is silent until the end of the movement, where the procession song is heard again.

Adolf Nowak writes about this in Fluchtpunkt Italien:

Berlioz shows how the protagonist, in the form of the solo viola, finds something other than what he himself

brings in. They are the manifestations of what cannot be ruled: the “outgrowing” of mountains, religion, love, and, finally, the horror of evil. Also, the music shows how he adapts to these experiences: the spatial expanse through “his” theme, the faithful and the lovers by contrasting and tuning into their melody; the evil, despite its fascinating presentation, by not tuning in and by reflection of the past good.

brings in. They are the manifestations of what cannot be ruled: the “outgrowing” of mountains, religion, love, and, finally, the horror of evil. Also, the music shows how he adapts to these experiences: the spatial expanse through “his” theme, the faithful and the lovers by contrasting and tuning into their melody; the evil, despite its fascinating presentation, by not tuning in and by reflection of the past good.Berlioz was not attached too closely to his literary work. What was important to him was the mood, character, and feeling that linked his Harold en Italie to the hero of Byron. When the harp sounds in the first movement, reference is made to Childe Harold's Pilgrimage:

But when the sun was sinking in the sea,

He seized his harp, which he at times could string,

And strike, albeit with untaught melody,

When deemed he no strange ear was listening

He seized his harp, which he at times could string,

And strike, albeit with untaught melody,

When deemed he no strange ear was listening

Performances and reworking

Although the previously discussed premiere was a complete success, following it, Berlioz decided to conduct his plays by himself.

On February 4, 1937, Lionel Tertis as a soloist, made his last public appearance as a soloist. Harold en Italie was performed with the BBC Symphony Orchestra, conducted by Ernest Ansermet.

In 1944, the first studio recording of the work was performed by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, featuring William Primrose as a soloist. It was conducted by Serge Koussevitzky.

Harold en Italie was reworked in 1836 by Franz Liszt for piano, accompanied by viola.

Sources:

https://www.ndr.de/orchester_chor (PDF)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harold_en_Italie

http://gutenberg.spiegel.de/buch (Buch einsehen)

https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pifferari

Vanishing point Italy: A decree for Peter Ackermann, edited by Johannes Volker Schmidt and Ralf-Olivier Schwarz

http://www.viola-in-music.com/Harold-in-Italy

http://www.helmut-zenz.de/berlioz

* Dallas Kern Holoman, Catalogue of the works of Hector Berlioz, (= Hector Berlioz. New edition of the complete works, Bd. 25), Kassel u.a. 1987, S. 138 ff.

**Pifferari: Shepherds from Abruzzi, who played reedpipes, bagpipes, and sang monotonously. During Christmas time, they came to Rome to play in front of pictures of the Virgin Mary.

Keith Dunn wrote on 10.05.2017 at 03:10

Several years ago I attended a night of Berlioz & Pachelbel performed by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Harold en Italie captivated me with the beautiful images brought forth by the then principal violist Reed Harris. The mental image produced with eyes closed by the beautify soothing rhythmic sound of the pilgrimage climbing the steps is etched in my memory. Love Berlioz!

Wendy Field wrote on 09.05.2017 at 18:13

One of my favourite pieces of music. Berlioz has wonderful melodies, and is a master orchestrator.

Karsten Dobers wrote on 22.04.2017 at 21:00

„Special Project“ part in the blog: “Harold in Italy” now exists in a new version for viola and organ....

| Special project by Karsten Dobers |

| Sheet music in our shop |

Harold en Italie

for Viola and Piano

Symphony in four movements with viola solo, with finger movements and bow strokes by Fréderic Lainé

» To «Harold en Italie» in the shop

| You may also be interested in |

Airat Ichmouratov

About Life and Work and Effect (Part 1)

Practice or talent? What makes for a great musician?

| Blog overview |

» To the blog list

| Newsletter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our newsletter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our newsletter will keep you informed.» Subscribe to our Newsletter for free

Visit us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.

Visit us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.» To Facebook